Pushpamala: The original disruptor | Mint Lounge

[ad_1]

Few artists have brought together humour and feminism like Pushpamala N. Forty years into her practice, the contemporary artist is one of the leading voices on the concept of photo performance in the country

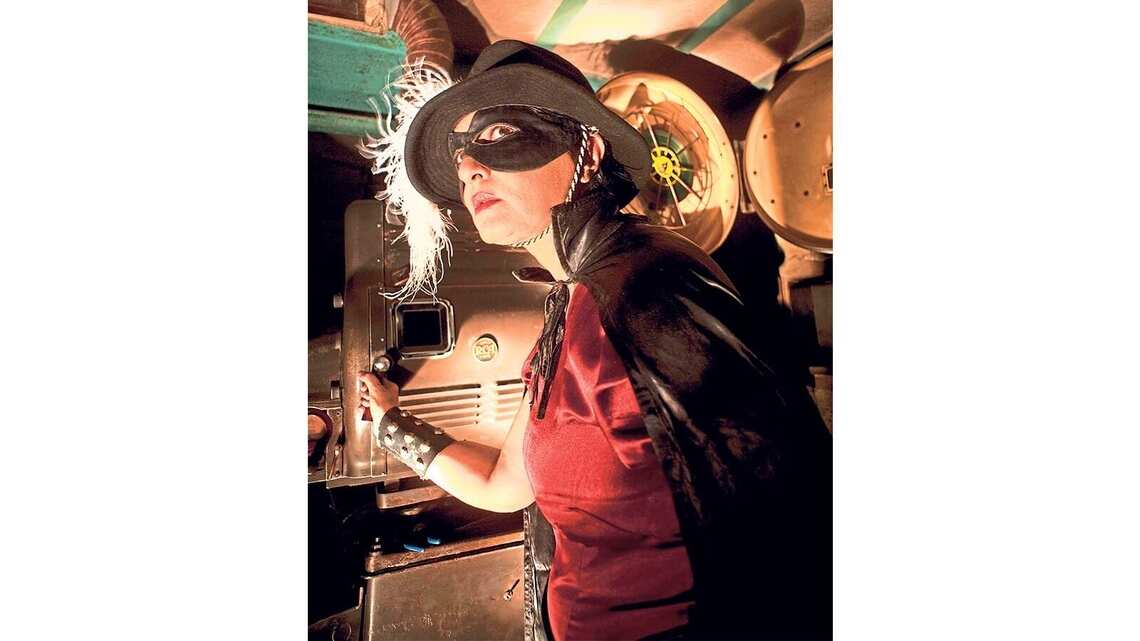

For the past few years, I have followed the Bengaluru-based artist’s photo masquerades with great interest. She morphs in and out of characters in elaborate photo performances that are often a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the realities of contemporary society. In some, she is a goddess incarnate—taking on the persona of Mother India—while in others she is a masked intruder, a chain snatcher, a woman from an indigenous tribe, with her arm outstretched for measurement, in what looks like an ethnographic study by the British colonialists.

You never know in what form or role you will see Pushpamala next. It all depends on which part of her subconscious—in which she has filed away memories, conversations and experiences—lights up at a given point in time, in response to the reality of a particular moment. And therein lies the wonder of her practice, making it almost chimera-like. Her work is based on the idea of “re-enactment”, staging, and the questioning of established tropes of cultural memory.

Pushpamala’s photo-performance work, in which she creates “photo-romances”, or tableaux, is truly one of a kind. Reflecting on her body of work over 40 years, one can say with confidence that there are very few parallels in the way Pushpamala imbues deeply feminist narratives with humour. Though she draws on iconography from Indian myths and art history, her practice remains firmly rooted in the contemporary, earning her the title of “the most entertaining iconoclast of contemporary Indian art”, among others, by galleries such as Nature Morte.

In each of Pushpamala’s photo-romances, the body becomes the site of work. Over a call from Bengaluru, Pushpamala, 66, describes her work as being feminist from the very outset. “I wanted to focus on the woman’s body and her narrative from the beginning, from my earliest sculptures. There is not enough of women’s perspectives out there—the way they see themselves and perceive history from the female gaze,” she says. To achieve this, the artist incorporates scenes from the daily routine and the labour put in by women, in her work.

Also read: Artist Lakshmi Madhavan weaves layered narratives around the body in kasavu

The fact that the artist makes herself a part of the composition changes the engagement with the viewer. So, by staging a film still, of the late Tamil Nadu chief minister and actor J. Jayalalithaa, in action gear or representing a glamorous alter ego of a middle-class housewife, she places herself as a layer between the underlying image and the viewer, changing the meaning of the original or pre-existing visual.

According to Peter Nagy, founder-director, Nature Morte, it is the timing of her practice that sets her apart. “She is ahead of her time. No artist from her generation, who had studied painting and sculpture, was doing photo performances—that too before the advent of digital photography and Photoshop. She was very prescient that way,” he says.

THEATRE OF THE ABSURD

At Bikaner House in Delhi, you can see an example of her staging of a scene shifting the viewer’s perspective in videos such as Rashtriy Kheer And Desiy Salad, which is currently playing at regular intervals. This 2004 work by the Bengaluru-based artist is a playful and ironic look at the modern Indian family, as imagined by the citizens and the government in a newly-independent nation. The video begins with a hand leafing through a collection of recipes, cut out from magazines and stuck on to pages of a notebook. Soon after, a family comes into the frame: the father, a military man, a playful 9-10-year-old son, and Pushpamala as a pregnant mother. The story seems to be set within a classroom, with each member coming to the board and writing random things—lists of priorities, lessons from a history book, memories of marriage and motherhood.

Suddenly, the board is full of different sets of text which come together as the absurd—military strategy such as “digging fire trenches and weapons pits” is followed by the steps required to preserve mango and childish doodles by the son of birds perched upon the weaponry drawn by his father. The blackboard, then, becomes a site of personal histories, political realities and the complexities of family life in modern India that exist between the two.

Also read: Eight artists come together to create a unique feminist poster-zine

‘Kichaka Sairandhri’, 2013, (after an 1890 oil painting by Raja Ravi Varma), photography by Clay Kelton, cast, Cop Shiva and Pushpamala N. Courtesy: the artist

Rashtriy Kheer And Desiy Salad is part of a video programme, Perpetual Transfers, which is currently being hosted by Anant Art Gallery under the banner of the exhibition Mycelial Legacies. It has been curated by Najrin Islam and looks at experiments in moving images by 20 artists from different generations who have graduated from the MS University of Baroda, Gujarat.

In a different part of the Capital—the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), Saket—you can see a different kind of Pushpamala spectacle. In one of the visuals, she is present as Lady In The Moonlight, a re-enactment of the popular 1889 Raja Ravi Varma oil painting. These works are being shown as part of Pop South Asia: Artistic Explorations In The Popular, a major exhibition by the KNMA and the Sharjah Art Foundation that showcases 50 artists from the region who are addressing complex issues facing the self, society and the politics of the everyday through irony, play and humour.

In fact, the very idea of performance is, to her, a feminist one, pushed by feminist artists in the US in the 1960s. However, unlike them, Pushpamala doesn’t use the physicality of the naked body, as seen in performances from that time, as a means to do away with patriarchal shackles. She is more interested in the social and political body. “The body is also a costume, with the persona and identity as masquerades. I use humour a lot. That is also something that has been denied to women. A lot of feminist work is about victimhood, which I find boring. I use humour instead of direct aggression and make things playful,” explains Pushpamala.

THE PERSON BEHIND THE PERSONA

A conversation with her allows me to make the connections I have been seeking between the person and the practice. For one, it becomes apparent that the humour in her work is not a result of deliberation. Rather, it stems from her own personality. Her humour is subtle, never in-your-face. For an artist who tackles complex ideas of the nation and womanhood, she doesn’t take herself too seriously. In fact, Pushpamala is never shy of showing her vulnerable side. “I constantly ask myself why I have to doubt myself all the time,” she says. “I think most artists feel like that. Psycho-analyst Shailesh Kapadia had this theory that artists are so embarrassed by their work that they have to overcome great initial resistance to proceed!”

Also read: 19 works that you simply must see at the India Art Fair 2023

Pushpamala wasn’t always constructing photographic images. She trained as a sculptor at MS University, completing her bachelor’s degree in 1982. K.G. Subramanyan, Raghav Kaneria and Bhupen Khakhar were some of the influences on her at the time. The artist’s first solo show, featuring terracotta and papier-mâché, took place in Bengaluru in 1983—2023 is the 40th year of her overall artistic practice.

In her early sculptures, Pushpamala was interested in creating an indigenous language based on an essential idea of “Indianness”, using folk art references. “(However), a new language had to be used to express the sharp disjunctures and fragmentations in the tumultuous realities around us,” she wrote in a 2011 piece, titled Towards Cutting Edge Art: Definitive Attempts, on the shifts in her practice. In the early 1990s, she made a series of installations, Excavations, as a response to the events that followed the destruction of the Babri Masjid. This marked a move from figurative sculpture to a conceptual approach, where “I made objects using thrown away papers and cheap found material”, wrote Pushpamala. She shifted organically towards conceptual art, using photography and video in the mid-1990s to create tableaux and photo-romances in which she casts herself in various roles.

Pushpamala N. getting ready to perform, as Kaikeyi. Courtesy: the artist/Chemould Prescott Road

The roots of this lie, perhaps, in her childhood, when she saw her mother, N. Vanamala, act in an amateur theatre club for women in Bengaluru. Her mother, a tall personage, would often take on male roles. In What’s In A Medium: Photo-Performance As A Feminist Medium, an essay published in Motherland: Pushpamala N’s Woman And Nation (Roli Books, 2022), Karin Zitzewitz examines such photos from Pushpamala’s childhood. The kind of performances that the artist’s family participated in were different from the usual Ramlilas. “Here, we have an altogether looser and more worldly sense of play…. A woman takes on the role of a hero. A young child awkwardly impersonates an old man. A girl presents an ideal, virtuous version of herself,” writes Zitzewitz.

Later, artist-teacher-friend Bhupen Khakhar, and the playfulness of his “faux advertisements and queer photo performances”, served as an inspiration. Pushpamala was not interested in being a photographer, her interest lay in the potential of the photo as an object. And her work takes on new relevance in the digital art age, powered by the likes of Midjourney and other Artificial Intelligence (AI) programmes.

Also read: How do language barriers impact artists?

Varun Gupta, director, Chennai Photo Biennale, says AI has been changing the way images are made, even questioning what an image is. “Pushpamala (who curated the 2019 edition of the biennale, titled Fauna Of Mirrors), challenged this very question with her curation for the biennale and across her bodies of work,” he adds.

THE PHOTO-ROMANCES

Her tryst with performative photography started with Phantom Lady Or Kismet (1996-98), in which she recreated a set of noir-film photos of herself, in collaboration with friend Meenal Agarwal, as a masked adventurer. The character was based on Fearless Nadia, or Mary Ann Evans, one of the first stuntwomen in the Indian film industry; the series was first shown at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai, in 1998. “This re-invocation of Evans challenged the conflation of the action genre with the masculine,” states an article on the website of the Museum of Art and Photography, Bengaluru.

Another important work by Pushpamala is the ongoing series, Mother India, in which she looks at the nation personified as a mother and goddess. Monica Juneja and Sumathi Ramaswamy, who edited Motherland: Pushpamala N’s Woman And Nation, describe the work as “feminist interventions made by this critical artist into an ongoing interdisciplinary dialogue about nationalism and the woman’s body”.

Native Women Of South India: Manners And Customs (2000-04) remains one of her most significant series, realised as a collaborative project with British photographer Clare Arni. The idea was to create different types of images of women from different sources.

‘The Native Types/Criminals’ (after a 2001 newspaper photograph) from the series ’Native Women Of India: Manners And Customs’. Courtesy: the artist/ the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

“There was continuous research—physical research from books and periodicals—as I didn’t know how to search on the internet at that time,” she says. The project took four years and saw 14 shoots—with each shoot needing about four or more months of production work. The post-production took a lot of time as Pushpamala had to keep going to Mumbai to get the images printed. Over time, Pushpamala and Arni had so many reference images that the project expanded into four series she later titled The Native Types, The Ethnographic Series, The Popular Series and The Process Series, making all the images ethnographic. “These playfully critiqued the original reference images and deconstructed them, while referring to various histories and modes of photography and image construction,” she says. The final project has more than 200 photographs, edited from the hundreds taken.

Also read: India Art Fair 2023: Designer Vikram Goyal debuts with new set of sculptural pieces

In fact, most of Pushpamala’s series are long-term projects, often spanning years between ideation and post-production. This was also the case with Paris Autumn. The film, made entirely from still photographs in 2006, took the form of a gothic thriller. It was exhibited as a cinematic installation, with photographs from the film printed as different kinds of film publicity material. The gallery space transformed into an Art Deco theatre.

She was in Paris for a residency in 2005 when she met a young French photographer, Cedric Sartore, who had just graduated from Ecole des Beaux-Arts and expressed a desire to work with her. Pushpamala asked him to shoot some visuals for her but he only had a still film camera. “While I was wondering how to edit still photos into a video, artist V. Viswanathan, who is based in Paris, came to my rescue. He told me that it takes a human eye three seconds to really see an image properly. So I used that as a benchmark to plan the number and duration of the shots,” she reminisces.

After having shot the film, Pushpamala got the footage back to Bengaluru and worked with film editor Sankalp Meshram in Mumbai. When the artist was thinking about how to structure the mass of material, Meshram recommended the film Vivre Sa Vie by Jean-Luc Godard, about a sex worker in Paris, which was structured like a diary, divided into chapters. Pushpamala found the structure interesting. But this was well before digital technology became a norm and the process of putting the film together in this format took a long time. She worked for a year to edit this film, which brought together personal experiences of Pushpamala’s stay in a mansion, once inhabited by Gabrielle d’Estrees—mistress of Henry IV—with fictional flourishes of visiting apparitions.

The Arcades Project by Walter Benjamin, which puts together a portrait of Paris in the late 19th century through the eyes of a flâneur (stroller), in the form of a series of quotations, was also a major inspiration for the film. “The genre of the ghost story seemed very apt. In the film, an apparition keeps pointing to the forgotten violent history of Protestant-Catholic wars in 16th century Paris, which I juxtaposed with the 2005 race riots in France ,” elaborates Pushpamala.

Also read: Victory City review: A grand historical, Rushdie style

‘Motherland (Where Angels Fear to Tread)’, 2011, diorama with store mannequins dressed in historical Mother India costumes, with props, arranged against a painted backdrop of a palace. Courtesy: the artist

NAVIGATING NATIONALISM

With series like Mother India, which remain deeply political works—even with the underlying humour—how does she navigate the current environment of nationalism? Pushpamala maintains that she has long been interested in the idea of the nation state and the place of women and marginal communities in it. “Sometimes, they are very funny, like the Phantom Lady photo-romances that look at the place of women in the city, where they function like ghosts or phantoms in the public space,” she says. In the Mother India series, she studies the history of the development of images that describe the changing ideas of nationhood. “The Arrival Of Vasco Da Gama (2014) looks at the moment in history which started the era of European colonialism and what is called the modern age. I use humour, wit, satire, cultural memory and a lot of references from different disciplines. At one level at they can be easily read and enjoyed, but also give rise to some deeper thoughts and questions,” she says.

A lot of her work uses the idea of the stage, and is replete with references from theatre. Often, she would end up buying “theatrical things” during visits to Delhi’s Chandni Chowk—necklaces, masks—which she didn’t know how she would use. “But suddenly an idea clicks and all of these backdrops and props fall into place. One thing leads to another through organic connections,” says Pushpamala.

She works like an archaeologist, excavating layers of meaning in all that she reads and researches. Her thoughts often pull her in different directions. For instance, she has just started on a huge body of work, but parts of it have become separate bodies, embarking on their own trajectories. “Every time I start off with something, it slowly grows into something else,” she says.

BACK TO SCULPTURE

Last year saw her return to sculpture with two exhibitions, Epigraphica Indica at Gallery Sumukha, Bengaluru, in April and Documenta Indica, at Chemould Prescott Road, in November. Nagy maintains that the sculptural element never really went out of her work. “For her photo performances, she creates costumes, sets, objects herself, and with the help of craftspersons. The only thing is that they have never been sold as art objects,” he says.

The roots of the monumental series Atlas of Rare And Lost Alphabets—a set of a hundred copper-plate inscriptions, which was showcased at the two exhibitions—date back to 2015, when she discovered tamrashasanas, or ancient copper-plate land records, while visiting an archaeological museum in Bengaluru. She then learnt the elaborate and extensive technique of etching and patinating copper sheets. The inscriptions on the copper plates were written in ancient, lost scripts from the subcontinent and were displayed in scrambled order, in such a way that they made no sense. To her, they became like mysterious records from an unknown time: fake histories, Dadaist nonsense texts, or hidden codes. It took her three years to finish the work.

In 2008, when she was invited to an international sculpture symposium in Gwalior, she had protested, saying that she had not worked with the art form for ten years. However, once there, she made the first set of cast bronze bahi khatas or traditional cloth bound ledgers she found in the market, titled Archives, in 2008. This connected to the time when she had used the image of books in her Excavation series in the 1990s. “I was later invited to one recently in Uttarayan in Gujarat in 2020 when I made another set of cast bronze ledgers which I called ‘1713- 2006’. It is like a fictional archive in a museum recording the history of communal riots in the state,” says Pushpamala

Also read: Tanuj Solanki’s new crime novel walks Mumbai’s mean streets

Pushpamala added her unique voice to works like Nara, a set of copper etchings framed like school slates, featuring powerful statements like “Pinjra Tod” and “Ideas are Bulletproof”—the latter created in solidarity with her late friend Gauri Lankesh—and documenting the recent protest slogans and poetry in India. The same technique used in the illegible Atlas tablets was turned into a language of resistance in these works.

There are threads that connect this new body of work with her past creations—for one, there is the notion of the archive or inventory and the element of the performative. Pushpamala realised this herself while working on Atlas Of Rare And Lost Alphabets. During her research, she would find images of alphabets from ancient scripts on the computer and copy them into a notebook. Suddenly, an image from the film The Name of the Rose, of monks sitting in a medieval library copying manuscripts, came to her. “This whole idea of copying down something is such a pre-industrial concept. In art school too, that was how we were taught art. At that time, we used to find it boring. No one told us why copying something manually was important,” she says.

But now she finds it interesting, because one learns about the form and content of an image while copying it. “In fact, Walter Benjamin said that the best way to understand a book is to copy it in your handwriting! A lot of my performance work is about recreating existing images to understand their meaning and deconstruct them. Copying scripts on these etchings has been like recreating a part of my performance practice. I felt like one of those old monks,” Pushpamala laughs.

There are also linkages—in terms of strong feminist themes—with her past sculptural works, done at the outset of her career. Long before the Radicals enjoyed a resurgence in the art world, curator and cultural theorist Nancy Adajania had found an image of one of Pushpamala’s terracotta sculptures in the catalogue of the landmark exhibition, Seven Young Sculptors (1985), which featured early experiments in expanded sculptural practice. “To see a girl wearing a bra, something so everyday and yet rarely ever represented in Indian art, came as a pleasant surprise,” says Adajania , observing that the artist’s , terracotta sculptures from the 1980s explored the threshold of adolescence—an unusual subject—to start a conversation about gender roles, nascent sexuality, and, most importantly, about the vulnerability of the girl child. “Sadly, Pushpamala’s cherub-faced girls were labelled as ‘feudal’ by the Radical male sculptors, whose politics was inflected by a masculinist heroism,” Adajania adds.

However, these links and ties that bind the past and the present start evolving while the artist is grappling with the material and the process of creating the work. It is only after the work takes on some form that the artist finds some coherence. “My work usually involves a long series, done over a sizable chunk of time. Sometimes I do hundreds of works, which form parts of sets. When the series is finished, it has usually become much more complex than the initial idea,” she says. The audience is also very important, they can bring in new interpretations of the work that she had never thought of. “When I exhibited my photo-romance, Dard-e-Dil for instance, a young artist kept coming up to me and asking me why I had the sister figure in the love story. I told him it was a narrative device because I needed a sakhi figure to carry messages between the elder sister and her lover. He later told me that his father had married two sisters. He saw the younger sister as an erotic figure!”says Pushpamala.

————————

‘Good Habits’ (2016), on display at the 2019 show at Nature Morte, Delhi. Courtesy: the artist/ Nature Morte

Also read: Now a new club that shines the spotlight on glass art

A feminist artist first

To place Pushpamala’s practice in contemporary art history, one must look at shifts in the 1980s-90s, when feminist politics across the globe began to impact Indian women artists. Gayatri Sinha, in her essay Revisitations: Women Artists In India Since The 1990s, published in 20th Century Indian Art, writes about the marking of the ground of a national feminist discourse by artists such as Nalini Malani, Rummana Hussain, Navjot, Sheela Gowda and Anita Dube.

Malani began with painting and moved on to video and installation to elaborate on “what it means to be female through a panoply of characters from world literature and art”. Hussain examined the condition of a Muslim woman in society, also bringing in an element of the performative, adds Sinha. Dube and Gowda envisaged their own form of conceptual art, using objects as vessels to question sociopolitical events.

At the time, the artists, including Pushpamala, were breaking free of the convention to experiment with newer languages in art making. Together, they ushered in what came to be known as the “cutting edge” in contemporary art. Later, artists like Sonia Khurana, Shilpa Gupta and Sheba Chhachhi would take “gender and performativity” in newer directions. “Women’s practice (1990s onwards) moves from contemplation/examination of the social into the sexualised self in a free-flowing gesture and often uses the body as a location for enacting dreams, transgression and rage,” writes Sinha.

Pushpamala turned the cultural memory of the image on its head by placing herself in it. The perfect example would be her 2013 work Kichaka Sairandhri, inspired by the 1890 Raja Ravi Varma oleograph of Draupadi.

Curator and cultural theorist Nancy Adajania elaborates on the significance of the artist’s conceptual art practice. “From the very beginning, Pushpamala has experimented with both the material basis as well as the ideological underpinnings of her practice. Artists like her and Anita Dube could be seen as having defined for themselves the role and responsibility of artist-intellectuals,” she says. In the process, Pushpamala has emerged as an important polemical figure, Adajania points out, contributing to debates around issues such as “the representation of gender in so-called high art, folk and popular culture, and artistic resistance in the age of ultra-nationalism”.

[ad_2]

Source link This week, the news of acclaimed artist Pushpamala’s award of the renowned Padma Shri made India proud. I recently spoke to the prolific visual artist to learn more about her journey so far, and why she is being rightly referred to as the Original Disruptor.

Pushpamala was born in Karnataka and was mentored in art by eminent teachers in India and abroad, including the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. She went on to develop a recognizably distinct style, by combining the traditional and modern, urban and rural cultural influences.

Pusphamala has become a pioneer in a field of creative practice known as ‘appropriation art’. She reappropriates existing images to create new, often witty, images that challenge existing iconography and power structures. This technique has enabled a refreshingly progressive reexamination of the art of post-independence India.

Pushpamala’s innovation in art has earned her a list of accolades, including the German ‘Goethe Institut Fellowship’, the prestigious ‘Abraham Kaling Foundation Award’ and the ‘Vishwa Bharathi Award’. Now, with the Padma Shri, Pushpamala has made India proud yet again.

For all her achievements, Pushpamala remains an advocate for art with ‘meaning’, citing the need for an artist to take responsibility for what they create and the need for art to inform, to push boundaries and to challenge the status quo.

Indeed, Pushpamala is the embodiment of an original disruptor – a disruptor whose success proves that engaging, thought-provoking, art can withstand the test of time.